[draft] Signal Correlation Hurdle Rates For Profitable Trading

Introduction

X (formally Twitter) user @macrocephalopod 1 describes a derivation of the minimum required correlation between a trading signal and the target return for profitable trading. It is defined as a function of the signal Z-Score, forecast horizon return volatility and transaction costs.

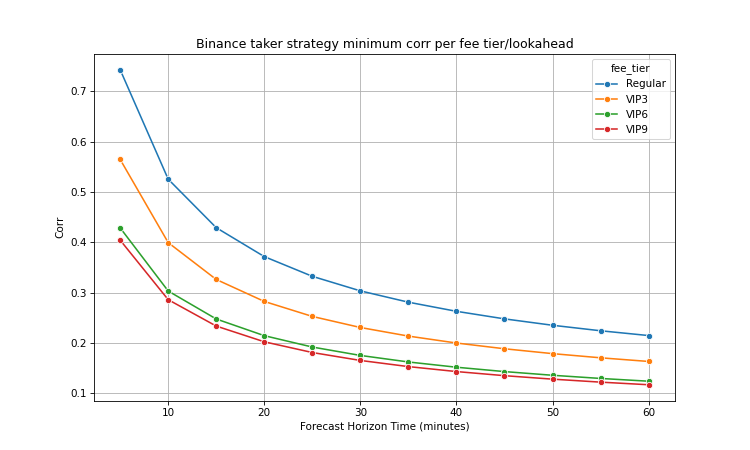

This blog post consists of a summary of this technique and applies it to historical Bitcoin price data. We visualise the minimum correlation for different combinations of transaction costs (exchange fee tiers) and target forecast horizons (via historical volatility).

Correlation, Alpha and Volatility

A quick recap on correlation before we continue, the (symmetric) Pearson correlation coefficient ($ \rho$) tells us if $x$ $(y)$ increases by one standard deviation, what is the expected response in increase of standard deviations of $y$ $(x)$:

$$ Corr(x,y) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{N} (x_i - \bar{x})(y_i - \bar{y})} {\sigma_x \cdot \sigma_y} $$

Grinold & Kahn 2 introduce a “refined forceast” $ \alpha $, in units of target return. Volatility is the target return volatility (standard deviation at our target horizon), Corr is the correlation between the trading signal and the target returns and Score is the Z-Score of a trading signal:

$$ \alpha = Volatility \cdot Corr \cdot Score $$

If we evaluate this function backwards we can see how we can covert an instance of the signal (Score) into expected target return using the correlation relationship described above. The (Z)Score is the signal transformed to have unit variance, we multiply this by the correlation coefficient to get expected target return in standard deviations and then we multiply this by Volatility to transform it back into the unit of returns.

In practise, the $ \alpha $ value is quoted without the score coefficient as it is variable over sequential evaluations of the forecast, it can change significantly tick to tick where as the correlation and volatility coefficients are assumed to be relatively more stable. The underlying distribution for the Score is commonly assumed to be a normal distribution, in which case we can make assumptions about how often we expect to see a signal over a certain magnatude (68-95-99.7 rule 3). Given the normal assumptions we can evaluate the effectiveness of a (Volatility $\cdot$ Corr) combination indepdendently, without getting bogged down by the raw Score values.

It’s important that our $ \alpha $ value reaches a magnitude large enough that it exceeds trading costs and that it does so frequently enough for us to acheive our target return on capital. We can improve the correlation between the signal and return via feature engineering and modelling. The Volatility coefficient can be tuned based on our target forecast horizon or the asset we choose to trade.

Minimum Correlations

Before continuing, we re-state the $ \alpha $ formula from above in more detail for comparison, for target return $y$ and signal $x$:

$$ \alpha = \sigma_y \cdot \rho_{xy} \cdot (\frac{x-\bar{x}}{\sigma_x}) $$

@macrocephalopod expands on this framework and forumlates the minimum correlation required to trade profitably ie. to exceed trading costs $c$ (eg. exchange fees, slippage).

He describes regressing forecast returns $y$ where the volatility coefficient has been expanded to allow for a time-varying lookahead, paramaterised by $\tau$. He then shows how the correlation formula can be re-written (see original post for detail) when $x$ has unit variance to realise $ \beta $ as the product of correlation and volatility, very similar to $ \alpha $ above:

$$ y = \beta \cdot x + \sigma \sqrt{\tau} \cdot \epsilon $$

$$ … $$

$$ \beta = \rho \cdot \sigma \cdot \sqrt{\tau} $$

Next, he introduces costs $c$ and calculates the signal correlation at which a $3\sigma$ signal will only cover costs, we need to exceed this correlation to make profits:

$$ 3\beta \le c $$ $$ \Rightarrow 3\rho\sigma\sqrt{\tau} \le c $$ $$ \Rightarrow \rho \le \frac{c}{3\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} $$

Assuming the signal follows a normal distribution, it will only exceed a magnatude of $ 3\sigma $ in 0.3% of periods - not enough to trade consistently. As such, as stated by the original author, values of 1.5x or 2x the minimum correlation is neccessary to realistically trade profitably - this allows us to reduce the signal threshold and exceed costs in a greater number of periods.

Evaluation on Binance Bitcoin price data

We look at the following (reduced) Binance fee tiers for taker orders and combine them with a constant slippage of 5 basis points (bps) for our cost variable $c$. The Total Fee is this estimate doubled, to account for both entering and exiting a position.

| Tier | Volume Requirement (USD, millions) | Taker Fee (Bps) | Total Fee (Bps) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 0 | 7.5 | 25 |

| VIP3 | 20 | 4.5 | 19 |

| VIP6 | 75 | 2.21 | 14.42 |

| VIP9 | 4,000 | 1.8 | 13.6 |

Using year-to-date (2024) minute bar close price data from Binance we calculate the one minute volatility as 7.5bps and utilise the $ \sqrt{\tau} $ multiplier to scale this to longer forecast horizons.

Most interestingly, the correlation threshold reduces as a function of an increasing forecast horizon. This is explained by the resulting greater volatility and hence magnitude of returns, while costs are held constant.

The minimum correlation for a signal on the VIP9 account is around 50% less than that of a Regular account but this is no surprise given the fees have reduced by around the same amount.

The notebook used to generate these plots is available here [^4].

Fee tier burn in

As an interesting exercise we investigate the “burn in” cost of a strategy which is only profitable at a higher fee tier and has to invest in an initial loss to advance to the required tier. We need to set some exta parameters: forecast horizon is 5 minutes, maximum time to complete the burn in is one week (2016 five minute periods) and the capacity of each trade is $30,000.

Example one - Regular to VIP3

We evaluate a signal with $ \rho = 0.496$, with an alpha of $8.3bps$, this is unable to beat Regular tier transaction costs at the $3\sigma$ level ($\alpha = 24.9$, $c = 25$) however on the VIP3 fee tier we can overcome transaction costs when $\sigma \gt 2.29$ and at this threshold we can trade in just over 2% of periods.

To go from the base tier to VIP3 we need to do 20 million of dollar volume, with our time and capacity constraints we need to trade 672 (33% of total period) times, to acomplish this effectively we can only trade a signal of (approx.) absolute value $ \ge 1 \sigma $.

At a minimum signal strength of $ x = 1 \sigma $, alpha is $8.3bps$ - after costs this is a loss of 16bps per trade. 16bps of 20 million - we lose approx $32,000 before advancing to VIP3.

Example two - Regular to VIP9

TODO: 1.5mm capacity is not realistic

With the previous examples capacity and time constraints we are unable to achieve the target volume of 40 billion. We update them to continue, time window is 4 weeks and trade capacity is $1,500,000. Given the increase in capacity, it’s a given that the slippage costs would also increase and affect our total fee values - but we will leave these as they are for simplicity.

We evaluate a signal with $ \rho = 0.405 $ and $ \alpha = 6.8bps $ - this allows us to exceed costs on VIP9 with a $ \ge 2\sigma $ signal (trading in approx. 5% of periods) and to exceed costs on VIP6 with a $ \ge 2.12\sigma $ signal (approx. 3% of periods). We do not exceed costs in the lower tiers, even at a $ 3 \sigma $ signal.

TODO: How to account for profitable signals instead of hardcoding 1sigma??

| Tier | Alpha (Bps, inc. costs) | Volume (USD, millions) | Trades | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | -18.2 | 20 | 14 | -36,400.0 |

| VIP3 | -12.2 | 55 | 37 | -67,100.0 |

| VIP6 | -7.62 | 3925 | 2617 | -2,990,850.0 |

| Total | -3,094,350.0 |

Summary

TODO

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1806436278067470524.html ↩︎

Grinold, R. C. and Kahn, R.N. (2000) Active Portfolio Management: A Quantitative Approach for Producing Superior Returns and Controlling Risk. McGraw-Hill, New York. ↩︎

68–95–99.7 rule, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/68%E2%80%9395%E2%80%9399.7_rule#:~:text=In%20statistics%2C%20the%2068%E2%80%9395,two%2C%20and%20three%20standard%20deviations ↩︎